Above Us, All Around Us

Project Context & Reflection

Image from Washington Post

"'This is a giant camera in the sky for any government to use at any time without our knowledge,' said Jennifer Lynch, general counsel of the Electronic Frontier Foundation, who in 2019 urged civil satellite regulators to address the issue of satellite imagery privacy." (Broad, NYTimes)

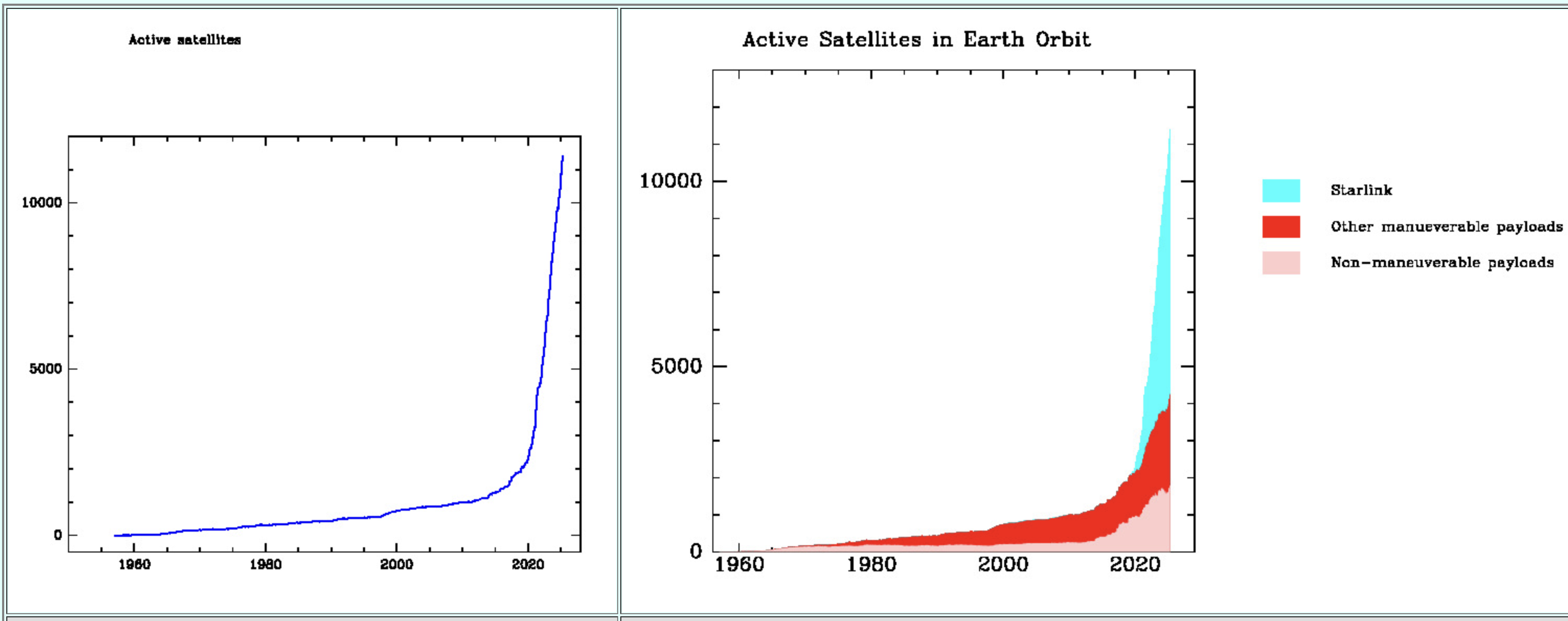

Currently, there are over 11,400 active satellites in orbit, according to Jonathan McDowell, an astrophysicist who works at the Harvard–Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics's Chandra X-ray Center. This number will likely continue growing exponentially as SpaceX's Starlink satellites grow in popularity with consumers and the US Armed Forces as well as Amazon's Kuiper satellites they have just introduced.

Yet, we have never once thought about all the satellites overhead. We take for granted that there are thousands of image-generating machines that help our maps, study the weather, and keep track of the land from above. Satellites do not seem real to us. They are distant, out of reach, invisible to our eyes, spoken for by higher powers beyond any of us.

With this project, our team wanted to combat this passive abstraction of satellites. As scholar Torin Monahan proposed, we want to develop countervisuality, a practice that "looks back" and pursues alternatives to totalizing regimes of state visuality. (Monahan) Using the power of solar, Arduino/MQTT protocol, and Raspberry Pis, we wanted to make the far-off information flow of satellite, aircraft, and radio more accessible and understandable to all ground-dwellers. We want to educate everyone about the analog, surreal, and revelatory nature of satellite surveillance.

On October 4th, 1957, Sputnik 1 launched. The Soviet Union made and sent the world's first ever man-made satellite into orbit while sending the rest of the world into awe. At that time, the satellite symbolized two contradicting forces: Techno-Optimism where people marvelled at the achievements of man and science but also Existential Fear that the Soviet Union or any motivated power could be watching, targeting, and waiting to strike from the heavens at a moment's notice.

As is well covered in many other sources, the United States joined the satellite party and kicked off a Space Race that developed satellites and other surveillance technologies that played a pivotal part in the Cold War between the Soviets and Americans. Culminating in the end of the Soviet Union and creation of the International Space Station as well as symbolized in movies like Contact (1997, based on Carl Sagan's novel), the cultural consciousness of techno/astro-optimism and satellites fades as 9/11, The Iraq and Afghanistan War, the 2008 economic crisis, and a new age of Big Tech takes over.

Even as the collective zeitgeist moved away from space, many satellites from the past decades still exist and operate. For our satellite tracking project, we chose 3 satellites originally launched from 1998-2009: NOAA 15, NOAA 18, NOAA 19. Primarily, we chose these satellites because they are the easiest to access via SDR, or Software Defined Radio. Software Defined Radio is using modern software to simulate the function of older analogue devices in receiving and decoding radio signals. In conjunction with feasibility, we chose the NOAA satellites because they represent an older era's ideals of developing technology for the public good with renewable sources that we should consider re-incorporate and prioritize in the world.

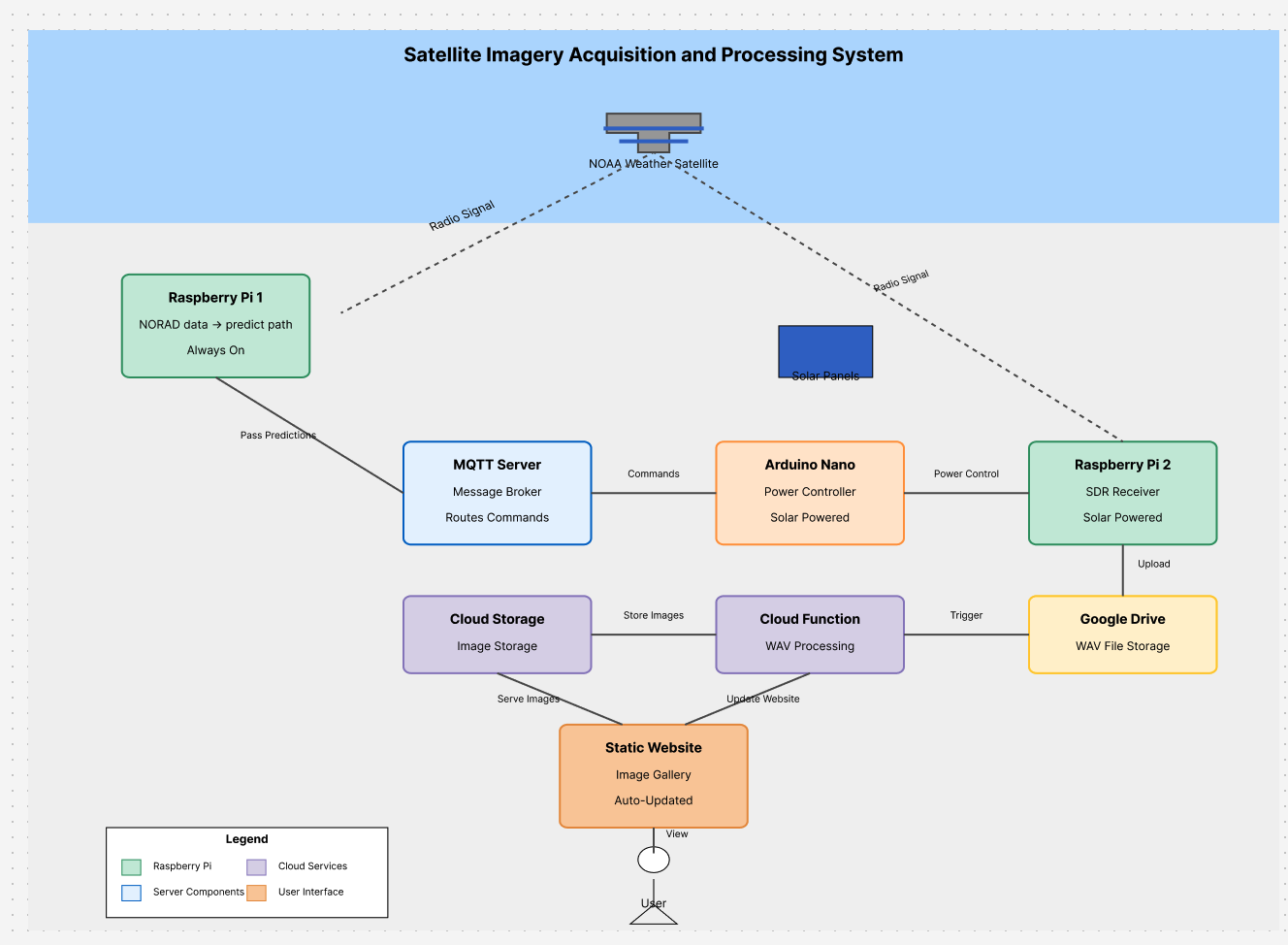

An array of solar panels/cells power each NOAA satellite (as well as most satellites). Our team thought it was fitting to communicate with other solar-powered objects when creating our own solar-powered automatic technology at the Brooklyn Navy Yard–with the help of Voltaic Systems by lending their batteries and solar panels to Jeff Feddersen's Energy class (read more here? - link to solar project documentation?). Our project consists of an Arduino Nano 33 IOT and Raspberry Pi with an RTL-SDR antenna installed at the Brooklyn Navy Yard, which are powered by a solar panel.

The Arduino at the Navy Yard listens to an MQTT server for messages from a second Raspberry Pi installed on the NYU ITP floor. This Pi uses a Python script based off of G-Predict software that pulls NORAD satellite orbital data from celestrak.org. This Pi detects an NOAA satellite about to pass overhead then sends MQTT messages to our Navy Yard Arduino, which is physically connected in Serial to our Navy Yard Raspberry Pi. The Navy Yard Pi then turns on and listens with the antenna. Then, this Navy Yard Pi sends the .wav recording of the satellite to our Google Drive. Then, we process and decode the .wav recording into an image, which you can see on the main page on this website.

Our biggest takeaway from this project is that while difficult, it is possible to use renewable energy and older technologies to reclaim a sense of empowerment over the technology above us–literally and figuratively. Plucking data and imagery out of space is an inspiring sensation. However, much like the launch of Sputnik (while not nearly as historic and groundbreaking), our project strikes at the tension of two contradicting forces: the optimism and hope of developing effective and useful technology versus the existential fear that satellite surveillance strikes. If a group of amateurs can develop an automatic system to tap into satellites in a few weeks, what are the multi-billion dollar companies and militaries able to do with much better equipment and resources?